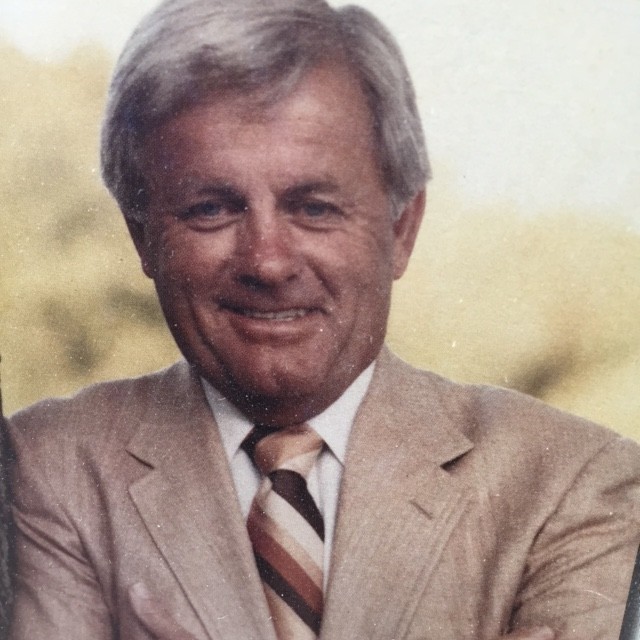

Bob McCurry was not my uncle, but we were second cousins. My grandmother worshipped him and considered him her second son. He was the best man in my parents’ wedding, and they both considered him a hero.

Bob McCurry

When I got out of the Army in 1969, I received a job offer from the Delco division of GM. My grandmother heard about it, got very upset, and contacted McCurry. I was hired by Chrysler. On my first day at work, the other trainee in the office approached me asking if it was true that McCurry was my uncle. I told him that he wasn’t but didn’t explain further. He responded with something like, “Well, anyway, good luck with that.” During my ten years at Chrysler I never talked to or met with McCurry. One time in those ten years when I was back in Detroit for training I went to his home for dinner.

Bob McCurry was an all-American center at Michigan State and captain of the football team three years in a row, which earned him a column in Ripley’s Believe or Not and was drafted by the Detroit Lions. Instead of playing professional football he stayed in school, earned an MBA in business, and was hired by Chrysler. In 1975 Chrysler products were not selling, and McCurry developed the first “Buy a car, get a check” cash-back incentive that would become a marketing phenomenon that remains popular today.

Four years after joining Yuki Togo at Toyota, McCurry had led the Toyota brand to its year with one million cars sold. Ken Meade, a Dodge dealer in Detroit, said that McCurry was, “one of the greatest car guys who ever lived.”

There was another side to Bob. He was driven. George Borst, the Toyota marketing manger under McCurry said, “No one ever left a meeting with Bob and asked, ‘What do you think he meant?’”

When I was looking to leave Chrysler I knew Bob was working at Central Atlantic Toyota, but I never called him or talked to him about Toyota as a possibility, nor had he contacted me. The Japan staff told me later that they were concerned about my relationship with Bob—but because I never used his name, and he made a call on my behalf, I was hired.

Lexus was the first time in 15 years that I would work directly with McCurry. My relationship with Bob was complicated, but I believe it did have an impact on the success of Lexus. I knew he wouldn’t fire me because of his relationship with my mother and father. Rightly or wrongly, I used that as leverage to push for things he did not want to do or did not agree with, such as having all-new Lexus dealership facilities and marketing at upscale operas and ballets. But mostly we disagreed about people. There were times when he made me lose sleep, cry, and throw-up, but mostly he made me better.

John French, the manager who came up with the Lexus name, got sideways with McCurry who was convinced John had violated the confidentiality agreement by telling his wife—who worked for Mitsubishi—secrets about Lexus. I defended John, and Jim Perkins wrote Bob a formal letter defending John, but to no avail. John decided to resign and went to work for Nissan. I couldn’t sleep the night John resigned and went downstairs and cried.

I believed that Lexus needed diversity in our managers and started hiring accordingly. McCurry did not approve and thought I was being weak. He got me on the telephone while I was in the Houston airport and ripped me up, down, and inside-out on the phone, telling me he wouldn’t sign anymore of the division’s funding requests unless I started hiring the people he approved. I was so upset after I hung up the phone that I went into the restroom and threw–up. He did not make good on his threat.

You will learn in the posts to come how he fought me for months over the Lexus dealership facilities, and we never really did get approval for our high-end marketing. But he didn’t stop us from implementing it either. There was no greater thrill than fighting with McCurry over an idea and getting him to agree to do something he originally refused to sign off on. If you really believed and fought for what you believed, he would relent.

McCurry loved the game of golf and was very good. We were in Japan with a joint Toyota and Lexus dealer council meeting. A golf day had been set aside. But there was a raging typhoon outside. Nevertheless, Yuki was determined to play, and play we did. Jim Richardson, the Lexus dealer from Cherry Hill, New Jersey, was my cart mate. It was a par-three uphill, about 200 yards. We were driving into fierce wind and rain. Incredibly, Jim made the green, but I did not. I drove the ball about 150 yards, but the wind took the ball off to the left and down a steep hill in a group of trees. Jim stood at the top of the hill and pointed to the green. Cold, miserable, and disgusted, I picked up the ball and threw it on the green.

Someone behind me yelled, “Hey. I saw that!”

I spun around. It was McCurry in the other fairway. He was shaking his finger at me but smiling.

Cynthia once brought my mother and father to the Lexus office to see where I worked. They decided it would be a good idea to go see Bob. I told them it was really not a good idea, that he was far too busy, but my ever-efficient assistant, Linda, quickly made the arrangements. A sense of unease crept over me. This was not good. The rumors would fly. Things got uncomfortable when my mother started shaking her finger at Bob and scolding him that I was “overworked and underpaid.” Bob smiled politely and gently rebuked her, telling her that she was mistaken because I was actually “underworked and overpaid.” Then Bob turned to me and said slowly, “Isn’t that right, Dave?” I abandoned my dear sweet mother and meekly agreed with McCurry.

We were having trouble with Lexus dealers in upstate New York selling cars into Canada. McCurry had me call one of the dealers to have him fly out to California for a “personal meeting.” The three of us went into a conference room next to his office. Bob sat at the head of the table, the dealer to his left, and I sat to his right. McCurry quickly worked himself into a livid rage. I was horrified. Even my first sergeant in the Army had never talked to someone like McCurry was talking to this dealer. The windows seemed to be shaking. The dealer slumped down in his chair and lowered his head. McCurry paused for a second to catch his breath. He looked over at me. He must have seen the sheer terror in my eyes. He winked at me! The entire meeting could not have lasted five minutes, but it seemed like an eternity.

The dealer grabbed my arm as we staggered down the hallway and said, “My God, Dave, I’m never coming back here.”

“Don’t sell anymore cars in Canada, and you won’t,” I replied.

“Don’t worry, I won’t. And I’ll tell all the others,” he offered.

I complained to my father about how hard McCurry was to work for and how I had never seen a man so driven. He told me to be gentle in my judgments about people because you never know their real story. We don’t want others to know who we really are and what we have done for fear others will judge us harshly.

He told me Bob’s real story. Every one thought the scar on McCurry’s chin came from football, but it hadn’t. When Bob was 18, he and his sister, Josephine, and two other friends, Bill Pry and Sara Sirrages, went to the 1940 New York World’s Fair. They had to rush back to school, so Bob drove all night. Early in the morning, about a mile outside of Lewistown, he fell asleep and crashed into a bridge abutment. He received the scar on his chin. Bill (18) suffered serious head injuries. His sister Josephine (21) and Sara (17) were both killed instantly. Every time he looked in a mirror he was reminded of that terrible night.

How could he ever forgive himself or atone for such a tragedy? It was too painful to ever talk about in our family. I believe Bob’s unrelenting drive and restlessness was more about escaping his pain and trying to atone for his mistake than chasing success.

In November of 2006, Bob was in the hospital fighting cancer. I called him in his hospital room. He was suffering. He said he couldn’t talk and asked me to call back. I told him I was praying for him, but I’m not sure he heard me. It was the last time I talked to him. He died shortly after that call.

Looking back over those years, there were days when I didn’t know if I hated Bob McCurry or loved him. What I do know is that he was driven by an impossible burden of guilt. I wish I could have helped him. I wish we could have been friends, but circumstances didn’t allow it. Today, I miss him terribly.

“The one who knows much says little; an understanding person remains calm.”

Proverbs 17:27 (MSG)

My first real disagreement with McCurry came quickly. He believed I had the wrong secretary. He told me to get rid of her, but I refused.

(To be continued in “Get Rid of Her”)