In March of 1992, the Lexus dealers and associates traveled to Japan for the third National Dealer Meeting. This was the trip to Japan that had been postponed by the Gulf War.

This would be an opportunity for the dealers and associates to tour the Tahara plant, interface with the Japanese senior management, and get a taste of the Japanese culture. The star of the show would be the freshened LS400 that would incorporate forty improvements.

The Japan America Symphony Orchestra performed alongside the Japan Youth Orchestra and Choir while a panoramic video of the land and seascape of Japan and America played on a giant screen.

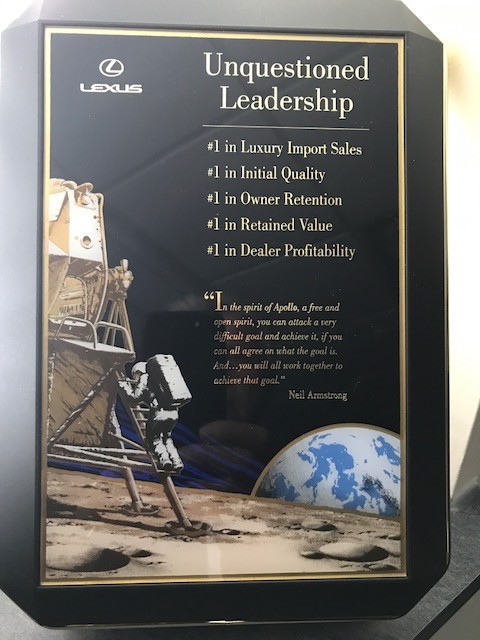

Rather than worrying about all the Japan-bashing that was going on, we decided to focus on the future and set five difficult goals for the division to achieve in 1992:

#1 in Luxury Import Sales

#1 in Initial Quality

#1 in Owner Retention

#1 in Retained Value

#1 in Dealer Profitability

Achieving these goals would take teamwork from everyone; from the engineers and plant workers in Japan to the sales professionals in America. We told the dealers and associates a story about teamwork:

On May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy set an unheard of goal for America. Before a joint session of the United States Congress Kennedy said, “I believe this nation should commit itself to achieve the goal before the decade is out of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely back to earth.”

Eight years later, Apollo 11 stood ready to attempt to land the first man on the moon.

Earlier in the year, the Russians tried to reach the moon with a satellite, but it missed and hurtled into deep space. Just three days before the Apollo launch, the Soviets had tried again to land a satellite but it crashed into the moon.

This man’s first trip to the moon was so highly anticipated that there were no hotel rooms available within seventy-five miles of the launch site. Three miles from the launch pad 300,000 cars and motorhomes were parked nose to rear for over ten miles. An estimated one million spectators came to watch the liftoff. The entire world was watching. An estimated television audience of over one billion people gathered around the TV to watch, for better or worse, the greatest adventure of all time.

Privately, many in the Apollo program set the chances of success at only 50/50. President Nixon had a prepared speech for the nation in case of a catastrophic failure.

Waiting on the launch pad sat a giant Saturn S4B rocket. She climbed 36 stories high and weighed 6,500,000 pounds. Liquid hydrogen, oxygen, and high-grade kerosene made up six million of those pounds. The liquid hydrogen, measured at 297 degrees below zero, was being pumped into huge jugs of the rocket. The magnificent white and silver rocket with an American flag on its side creaked and moaned as she waited on the pad. Huge chunks of frost formed on her walls and fell to the ground occasionally.

Three men were perched on top of six million pounds of explosives: Michael Collins, Buzz Aldrin, and Neil Armstrong.

At T-minus 8.9 seconds, the ignition sequence begins and four small flames light inside the rocket. A sudden flash of orange smoke blasts out the base of the rocket.

At T-minus 5.3 seconds, the main fuel valves open and a torrent of liquid oxygen burst through at a rate of three tons per second. Enormous flames roar from the rocket along concrete channels as an underground river of flames pour into the air upward and outward, engulfing the rocket.

At T-minus zero, the engines have developed 6.5 million pounds of thrust. The first deafening sounds come through the ground as the earth starts to move. The S4B builds to 7.5 million

pounds of thrust and the crackling sound of a thousand machine guns splits the air. The Saturn rocket levitates in place as nine holding arms weighing ten to thirty tons a piece hold back the S4B rocket. The earth trembles and shakes as the holding arms release. The sound waves create a physical force of thunder so great it is believed to equal the volcanic eruption of Krakatoa in 1883.

Collins, Aldrin, and Armstrong begin their 218,000-mile journey to the moon. They will travel at a speed of 21,000 miles per hour and, if all goes well, reach the moon in three days.

Apollo 11 achieves orbit 50,000 feet above the moon on July 20, 1969. The Lunar Module “Eagle” separates from the Command Module. No one knows what the next twenty minutes will bring—great triumph or great tragedy.

Back on earth, a decision must be made. Flight Director Gene Kranz tells the eight flight controllers he is going around the horn for a “Go, No-Go” to land on the moon. All are, “Go!”

The Eagle is controlled by a computer guidance system from 45,000 to 2,000 feet above the moon. This guidance system takes control and it rolls the Eagle over and begins its descent to the moon. The astronauts, their feet forward and laying on their backs, are looking back at Earth. The rockets are burning in front of them, slowing their descent at six thousand miles per hour. Six minutes into the descent, an alarm buzzer starts sounding. The landmark Maskelyn W is two seconds late on the horizon. The Eagle is two miles off-course.

Buzz Aldrin calls out, “Program alarm 1202.” The computer guidance system is signaling an overloaded condition. It’s complaining that it’s getting too much information.

All eyes turn to 26-year-old flight controller, Steven Bales. Aldrin repeats, “1202!” There is no response from Steven Bales. He must make a “go, no-go” decision to land on the moon. Impatiently, Aldrin calls out, “Give us a reading on the 1202 alarm!” It takes 19 seconds for Bales to make his decision. He overrides the alarm and shouts out to Kranz, “Still a go!”

Eight minutes into the descent, flight controller Bob Carlton whispers to Kranz, “Descent two fuel.” This is a code to warn the astronauts they are burning too much fuel.

Nine minutes into the descent, Aldrin calls out, “We’ve got an alarm 1201!” The computer guidance system is again complaining about being overloaded. Steven Bales overrides the computer a second time and shouts out, “Still a go!”

Ten minutes into the descent, 2,000 feet above the moon, Neil Armstrong takes over control of the lunar module. He drifts over the moon, burning precious fuel, looking for a place to land.

Carlton tells Armstrong, “60 seconds.” Armstrong has 60 seconds to land on the moon or the computers will abort the landing and fire the ascent rockets, sending the Eagle back to the command module. Carlton firmly says, “30 seconds.” With an estimated 11 seconds of fuel left, Neil Armstrong lands the Eagle on the moon at Tranquility Base.

One day later, Eagle lifts off the surface of the moon and on July 24, 1969, all three men return safely to earth.

A year after his trip to the moon, Neil Armstrong was asked what impact, if any, the Apollo mission had on the world. Armstrong expressed disappointment that the Apollo mission had little impact because people on Earth had missed the real message of Apollo.

Armstrong said, “That real message is that, in the spirit of Apollo, a free and open spirit, you can attack a very difficult goal and achieve it if you can all agree on what the goal is and you all work together as a team to achieve that goal.”

The real story of man’s first trip to the moon is not a story about rocket ships and outer space, but a story about teamwork and people working together to achieve a difficult goal.

After the meeting, all the dealers and associates were given plaques with Armstrong’s quote and the objectives for the year.

“It’s better to have a partner than go it alone. Share the work. Share the wealth.” Ecclesiastes 4:9 (MSG) In order to reach our goals, we knew our team needed to work together. It was a great reflection of the way God calls us to walk through life. We need each other to stay accountable and continue following the Lord’s plan for us. Read more about His plan and His love in the God of Hope book!

Lexus was getting well-established and many of the Japan staff were being called back to Japan. Cynthia and I decided to have a going away party at our home. It turned out to be a career-threatening event for one of the junior Japan staff members and it wasn’t his fault.

(To be continued in “The Fractured Cat”)